Doing science in disadvantaged countries that lack infrastructure and resources can be discouraging for researchers. That is why Abdus Salam founded ICTP: to help scientists from developing regions overcome lack of opportunities and isolation.

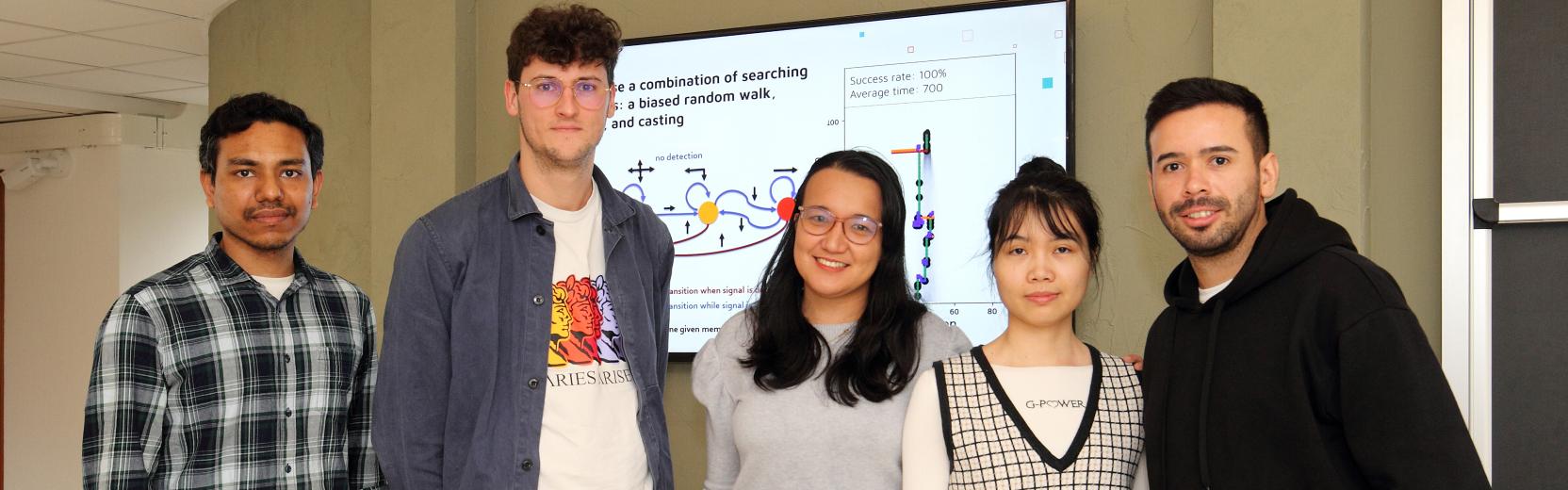

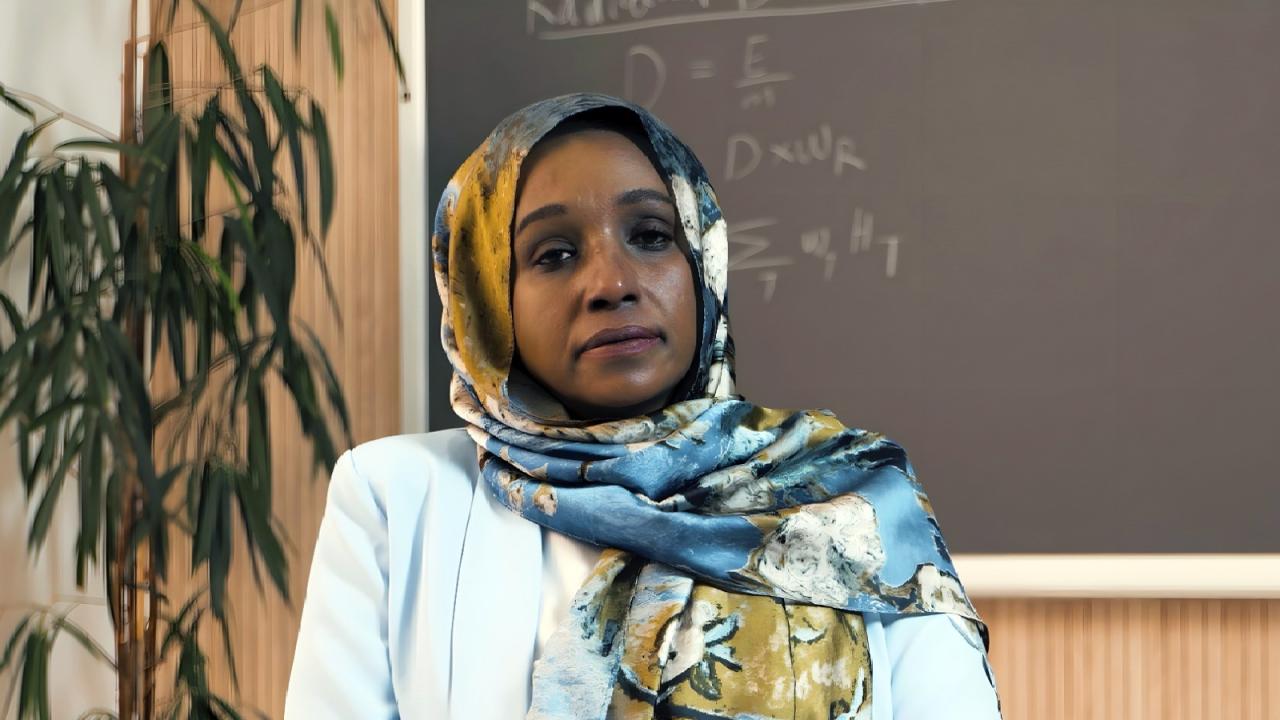

It was ICTP's reputation as an international hub for scientific collaboration that attracted Sudanese physicist Nada Abbas Ahmed, an assistant professor in medical physics at Taibah University, in Saudi Arabia. After a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in physics, she pursued a PhD in medical physics. During her doctoral studies she decided to apply to the ICTP Associates Programme. Since then, she has visited ICTP many times – first as a Junior Associate, then as a Regular Associate and since 2024 as an Arab Fund Associate, supported by the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development. As an Arab Fund Associate, she is entitled to visit ICTP three times over a three-year period, and to bring a student with her, who will also benefit from the ICTP scientific environment.

In this interview, Abbas Ahmed talks about her journey in science and about her passion for radiation imaging and for ensuring that maximum diagnostic power can be obtained from these techniques, all the while minimising their harmful impact.

How did you start your path in science?

Already in primary school I was more interested in mathematics and science than in other subjects. This interest continued in high school, and when I had to choose between math and biology, I chose math. This decision was very important for my career, because it is ultimately what led to my decision to study physics at university.

How did you decide to specialize in medical physics?

While at university, I attended classes where we did experiments in nuclear and radiation physics. It was fascinating. Imaging techniques are powerful tools used in hospitals to support accurate diagnoses. These techniques, however, often use radiation. The more intense the radiation, the more accurate the final image, but with a potential hazard for the patient and the medical staff involved. Seeing the power of radiation imaging techniques and considering their potential in medical diagnostics motivated me to seek a career where I could gain a deeper understanding of these powerful techniques and contribute to ensuring their safe and effective application.

Immediately after graduation I joined the radiation safety department in Sudan’s Atomic Energy Commission. There, I received specialized training in radiation dosimetry, shielding techniques and regulatory guidelines, and I worked closely with hospitals in projects involving dose optimization and radiation shielding. These experiences also gave me the opportunity to witness first-hand the challenges involved with radiation safety in my country. I realized that there was limited access to advanced technology and a need for greater knowledge. That is why I decided to start a PhD in medical physics after completing a master’s degree in physics.

What motivated you to apply for an associateship at ICTP?

Research in developing countries is very challenging for several reasons. In Sudan, we had limited access to equipment and to research collaborations, and few opportunities to attend specialized training programmes. This motivated me to apply for an associateship at ICTP. I first obtained a Junior Associateship, which was really a turning point in my career. Coming to ICTP gave me the opportunity to interact with leading experts in my field and to collaborate with other researchers. While at ICTP I also participated in workshops and training programmes. It was a very valuable experience, which is why I applied again when I had the opportunity. I am deeply grateful to ICTP for this programme and also to the Arab Fund for supporting my most recent visits to ICTP.

Did you have other opportunities to conduct research abroad at the time?

I carried out part of the practical work related to my PhD in Udine, Italy, as part of a programme funded by the IAEA. I worked at the hospital for three months, collecting data which I used for my PhD. That was completely independent of ICTP, although at that time I was already a Junior Associate at ICTP.

What do you work on now as a medical physicist?

My role is to help find an optimum balance between the accuracy of the images used for diagnosis and the risk related to getting those images. In particular, my research focus is on optimizing radiation levels in medical imaging, seeking a balance between reducing radiation exposure and maintaining image quality. I am working on improving imaging protocols and techniques, optimizing radiation doses and implementing safety strategies to ensure that patients receive their safest and most effective diagnoses. I also work on radiation risk assessment for workers who are exposed to radiation, helping to develop better protection measures in clinical settings. We work on real data that we collect in hospitals.

How do you carry out your work when you come to ICTP?

While at ICTP I went to the hospital in Trieste several times to meet the medical physicists there. They introduced me to their research and their work. Being at ICTP also gave me the opportunity to meet with other researchers, and that has already led to new collaborations.

A key feature of the Arab Fund Associateship is the possibility to bring a student with you during your visits. What does this opportunity mean to you?

It means that not one but two people will benefit from ICTP’s supportive environment and get access to ICTP’s advanced resources, visit hospitals in Trieste and meet other medical physicists. They may also benefit from workshops and trainings happening at ICTP while we are there. And of course we will be working together, and will benefit from some time dedicated solely to our research. In itself, this will be a boost to our collaboration.

Last year, it was not possible for me to come with a student because the time was too tight, and it was also challenging to leave Sudan. This year, however, I was able to bring a Sudanese student. I left my country in 2017, before the war started, but I have remained in touch with my former colleagues there, particularly with one student who was able to continue her studies in Egypt. I am glad she had the opportunity to visit the Centre, where we spent valuable time in discussion and working on parts of her research. She has greatly benefited from this opportunity.