It takes a closer look to realise that the kind of research done at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics is not only theoretical after all. Many experimental physicists hide in the corridors of ICTP’s High Energy, Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (HECAP) section, as they work quietly behind their screens to analyse data coming directly from one of the world’s largest and most powerful accelerators.

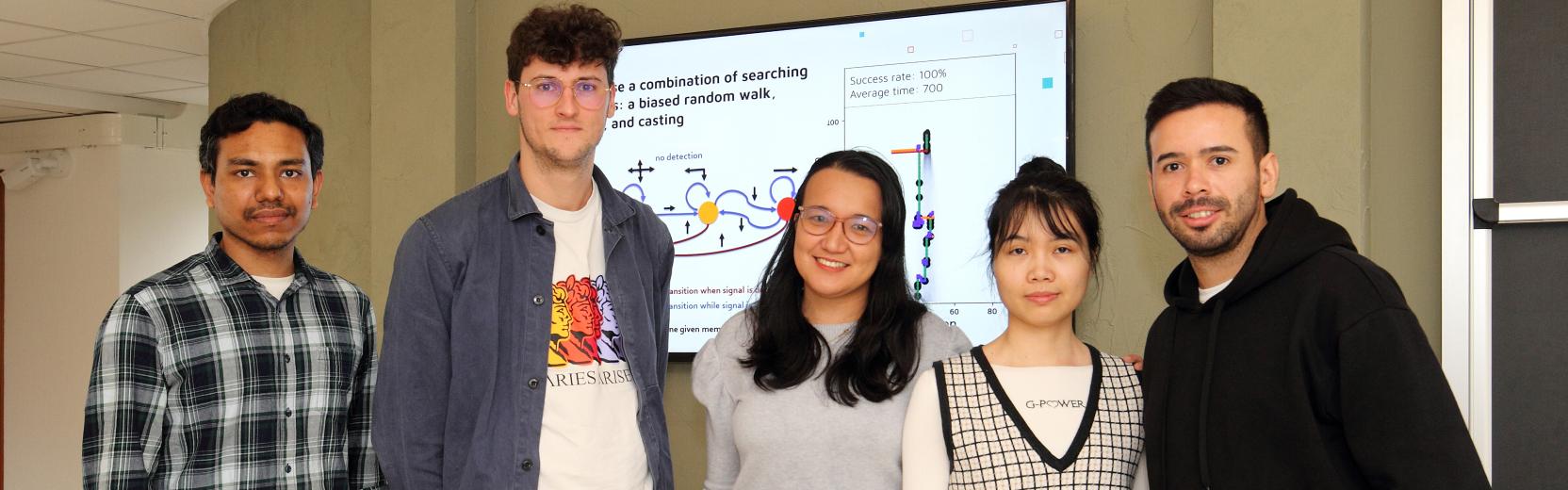

Launched in 2008 by Bobby Acharya, a research scientist at ICTP and the only theoretician in the team, and Marina Cobal, a professor at the University of Udine, the ICTP-Udine ATLAS group brings together the research efforts of scientists at the two institutes. The group works on the ATLAS experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC). In this 27 km ring located 100 metres underground across the Swiss-French border near Geneva, protons and ions are accelerated to unprecedented energies and made to collide, to investigate fundamental physics’ deepest secrets.

ATLAS is one of the four main particle detectors at the LHC accelerator. As a general-purpose detector, it is designed to precisely measure fundamental processes and search for new particles across a broad range of energies and masses. Researchers in the ICTP-Udine ATLAS group have been involved in the experiment since its early days and contributed to its most famous milestone in 2012, when the two main experiments at LHC detected the long-sought Higgs Boson.

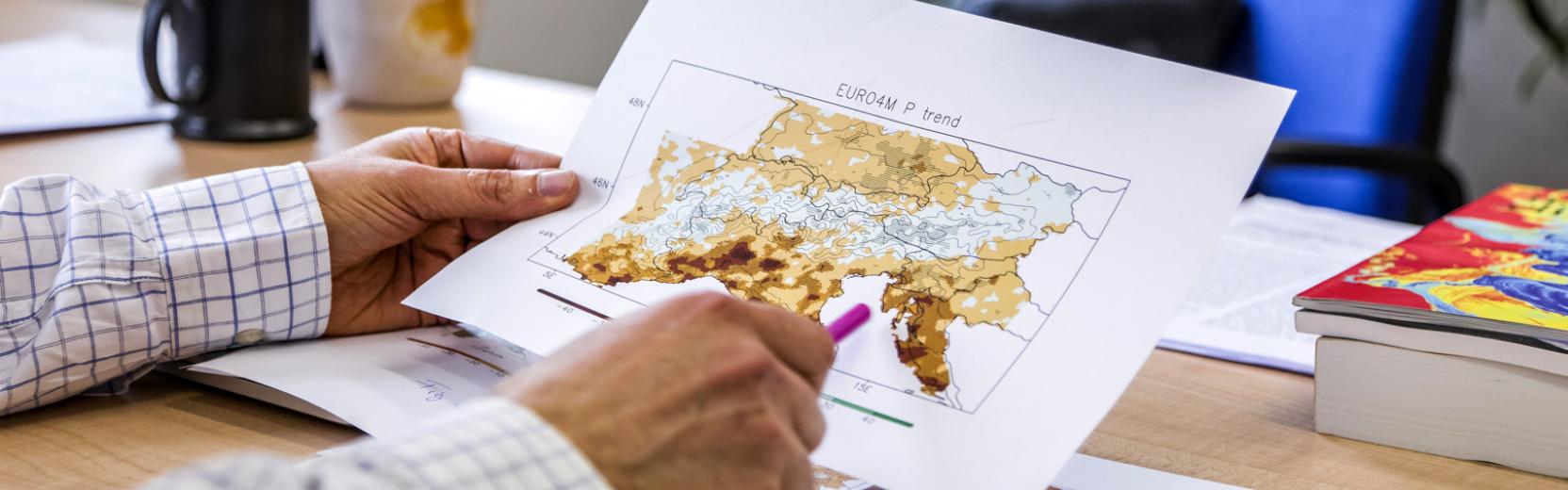

Since that discovery, the collaboration progressed into new, more ambitious phases. After the first upgrade of the accelerator, the LHC started a second phase of data collection, known as Run 2, which lasted between 2015 and 2021. During this period, proton beams reached a collision energy of 13 TeV — almost twice LHC's previous energy. The data collected in this phase allowed the precise characterisation of the Higgs Boson and the first observation of a number of rare processes. For these contributions, in April 2025 all co-authors of publications based on CERN’s Large Hadron Collider Run-2 data, including many members of the ATLAS group at ICTP, were awarded the 2025 Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics, receiving a prize certificate last October.

“Receiving the Breakthrough Prize affirms the value of years of technical, analytical and human work and is a profound honour for our entire community. It recognises the worldwide work of all researchers, not only of the ATLAS collaboration but also of over 13,000 researchers across the LHC,” says Mohammed Faraj, a postdoctoral researcher at ICTP and a senior researcher at the University of Udine.

In 2022, after a second major upgrade, the LHC entered a third phase of data collection, Run 3, to which researchers in the ICTP-ATLAS group are actively contributing. “As a group, we are focused on making precise measurements of Standard Model predictions, particularly in the area of top-quark physics, including single top, top-pair, and even rare four-top-quark final states,” explains Faraj. The Standard Model of elementary particle physics is currently the most successful theory describing three of the four fundamental interactions. However, despite the remarkable agreement between LHC data and Standard Model predictions, several observations — such as dark matter, the matter–antimatter asymmetry, and the fact that neutrinos have mass, to list a few — tell us that the theory is not complete.

“As we achieve new levels of precision in our measurements, we are also continually searching for deviations from the Standard Model, which could guide us towards a theory that better describes the physical world, covering the weaknesses in the Standard Model,” Faraj explains. For this purpose, experimentalists collaborate closely with theoreticians. “In our team, whenever we see a possible deviation from the Standard Model, we refer to Bobby [Acharya] and the other scientists in ICTP’s HECAP section to discuss our latest results and explore theoretical models that could test for new physics beyond the Standard Model,” Faraj adds.

“The search for new physics is both exciting and challenging. Every time we think we have found something new, we must conduct several checks to ensure that the data reflect a physical phenomenon,” Faraj says. “Furthermore, we are continually trying to improve our data analysis techniques. For instance, in several measurements and searches, we have integrated machine learning into our data analysis, which has enabled us to identify rare processes that had never been observed before,” he adds.

To continue their search for new physics, scientists will need to reach greater energies. “Because many theories beyond the Standard Model predict the existence of particles significantly heavier than those currently observable, we need to push the boundaries of particle physics to unprecedented heights and achieve higher collision energies for which larger rings are necessary,” Faraj explains. Pushing the boundaries further, the project to build a 91 km circumference accelerator that could succeed the LHC is already under consideration at CERN. If approved and all proceeds as planned, a first round of measurements could start at the end of the 2040s, opening a larger window into matter’s deepest secrets.