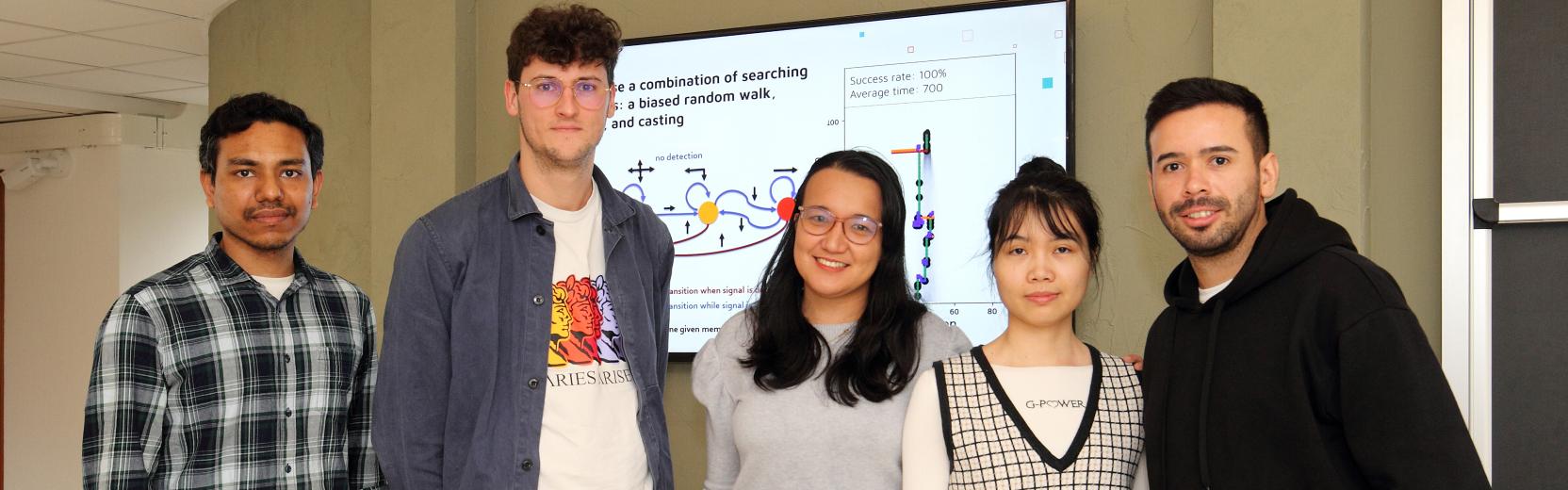

The Postgraduate Diploma Programme at ICTP was originally created to help students from the developing world consolidate their skills and knowledge, enabling them to continue in international higher education. Since 1991, 1167 students from 84 different developing countries have graduated from the Diploma Programme. ICTP is committed to addressing the gender imbalance existing in science and technology, and actively encourages female students to participate in the programme. Twenty-nine percent of diploma students over the last 12 years have been women, with the proportion of female students steadily increasing.

Deborah Osei-Tutu, a 2023 Postgraduate Diploma Programme graduate from Ghana, talks about her love for geophysics and plans for the future. She was the top student among those who completed Diploma studies in Earth System Physics, and was also the first recipient of a prize established by long-time friends and supporters of ICTP Qaisar and Monika Shafi for the top Diploma student.

Tell us a little about yourself.

I'm Deborah, and I come from Ghana. I completed my undergraduate studies at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) with a Bachelor of Science degree in Physics, and my diploma project here at ICTP is in Numerical Seismo-Mechanical modelling.

How did you discover your interest in physics?

My interest in physics began way back in high school. I loved the subject so much, because to me it’s the fundamental of all physical sciences. I was always fascinated by how physics could explain the complex physical processes of our universe, and then dedicated much time to reading physics. Interestingly, I wasn’t scoring the maximum grades in physics in high school. This was partly because we sometimes lacked teachers for a semester or more. In the high schools, physics teachers are scarce, a very common problem in Ghana.

Without a teacher, we had to study on our own, but that helped me to build more interest in the subject. And it challenged me, so then I decided, “okay, let me study physics, and also become a teacher to help these students.”

What did your friends and family say when you decided to study physics?

It took me a lot of time to really convince my family, because they felt that I should go into medicine or law, especially as a lady. In Ghana physics is not much appreciated. I applied to medical school at first, because I wanted to make them happy. But when I went for my interview, I voiced out what was in my heart and my preference of physics over medicine. Consequently, I studied physics in the university, and enjoyed it.

In the third year of university, I chose to specialise in geophysics, from the five options we had in the department. Again, I got intrigued by how with physics, we could probe into the internal structure, composition and internal processes of the Earth without having to open it up. In fact, there is no way we can dig up to the earth’s mantle or core to study it. I thought this was a good place to apply myself and study more. After graduation, I spoke with one of my lecturers about continuing in geophysics, and he suggested I applied to ICTP. I was quite reluctant, because I don't have a Master's degree, and I knew it would be intensive too. But I applied and got in.

What’s your thesis about?

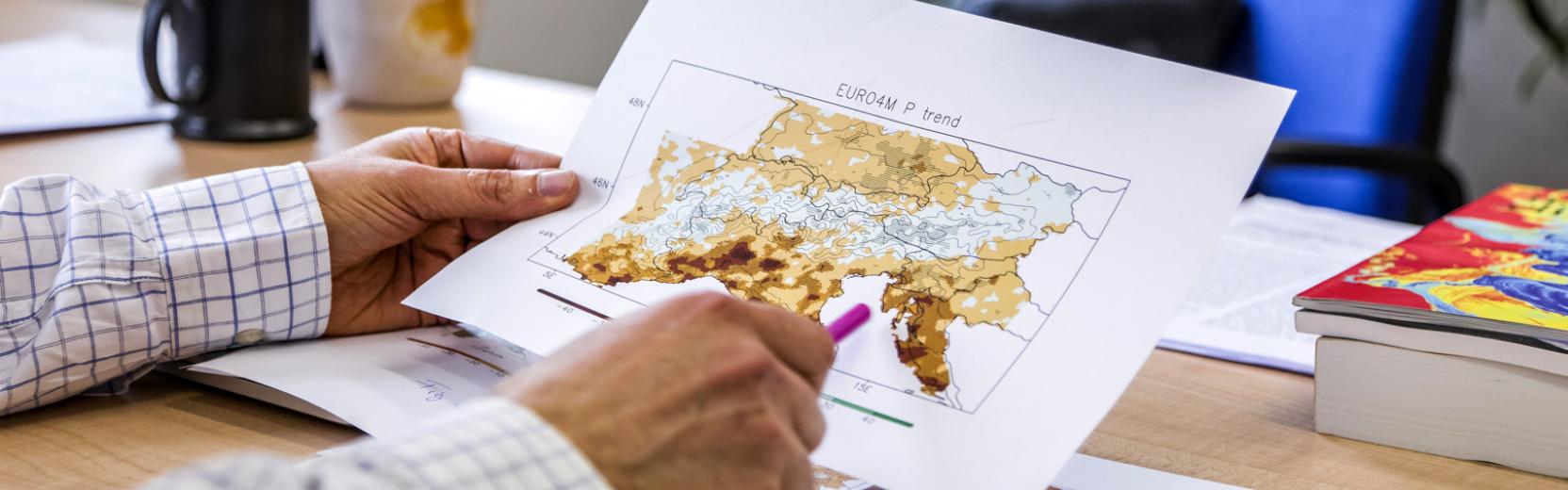

I’m working on the maximum expected earthquake magnitude from the interseismic scale with Abdelkrim Aoudia. Basically, we are using numerical modelling to simulate elastic strain energy stored at a transition zone and also simulate the slip along a fault using the interseismic length scales. We are going to apply this to the Main Himalayan Thrust in Nepal. This will be very useful for seismic hazard assessments in that area.

Who chose the subject for your thesis?

My supervisor suggested the research problem. I read through the literature material, and brought up the methodology to solve the research questions.

Were you interested in this particular subject before you came here?

No. In the solid earth group here at ICTP, we mostly focus on global seismology, tectonics, space geodesy and physics of volcanoes. In KNUST, the focus is on exploration geophysics using seismic, electromagnetic, geomagnetic and radiometric methods. So, it was different for me, but I love it because it’s all about the physics of the earth.

What are some of the career challenges that physicists face in Ghana?

Funding. A lot of researchers, with great ideas have abandoned their career to join politics or industry because of limited or no funding. In my opinion, Ghana has not come to the full realization of how important science and technology is to its national and socio-economic development. For many years the focus has been on other things and not science. Ghanaian scientists, or physicists particularly, receive less recognition and appreciation for what they do.

What are you doing next?

I’m going to continue my studies, to get my Master's degree and then PhD in computational geoscience at LMU in Munich, Germany. This is because here, I've developed a keen interest in computational modelling and programming.

What do you imagine happening in your career in the next 10 years?

After my PhD and getting more into research, I will certainly go back home because I absolutely want to setup an institute like ICTP in Ghana that does mathematical and computational physics and modern programming for geoscience. We have a lot of geoscientists because of the minerals and other earth resources there.

In 2019, I remember we took a tour to one of the oil companies, and the staff complained about inadequate computational resources and local experts. Experts in software development and management have chiefly been people from outside Ghana.

It’s also my great desire to be an advocate for female education, especially in physics. I sat in a physics class of 90 % male students and was never taught by a female lecturer during my 4-year undergraduate studies. Much more ladies have to be encouraged to pursue higher education in physics and science, and this I will passionately get involved in when I go back home.

What were the strengths of the postgraduate diploma program?

The courses were research-oriented, and I liked that so much because every one of my classes gave me a desire to do research. They showed what can be done, and the knowledge gaps in what has been done.

Additionally, I loved the occasional colloquiums and seminars. Although some of them were not directly related to my domain of study, I gained much knowledge in other disciplines. I will say, I have developed an appreciable ability to think in other fields and be multidisciplinary. In each part of the curriculum, I was very happy to learn more and also be inspired by what other scientists are doing. I am highly motivated to work hard and be able to do great and excellent research too.

I really like the multicultural community here. When I think about this, I really appreciate the fact science is universal. It doesn't depend on your background, race or colour; just like-minded people coming together to think and work.

Last but not least, the scholarship offered to us was absolutely a great one. Financial need was not a thing to worry about as everything was provided for. And so, success in our academic and research pursuits could not in any way be jeopardised by lack of funding.

How do you think doing the diploma has affected you as a scientist?

First of all, when I thought of my career in the past, I was very restricted. I didn’t see farther than I see now. I now have a broader view of what I can do with physics of the earth, even across disciplines. There is actually no limit, and this has changed my mind-set about academia.