Inequality is a key factor in any analysis of sustainability, although the way in which it is addressed varies widely depending on the approach and objectives of researchers. Complex systems scientists can use methods from statistical mechanics to study the interdisciplinary aspects of sustainability and inequality from a quantitative perspective. Matteo Marsili, senior research scientist with ICTP's Quantitative Life Sciences section, talks about ICTP’s efforts in this direction.

What is your work on inequality and complex systems?

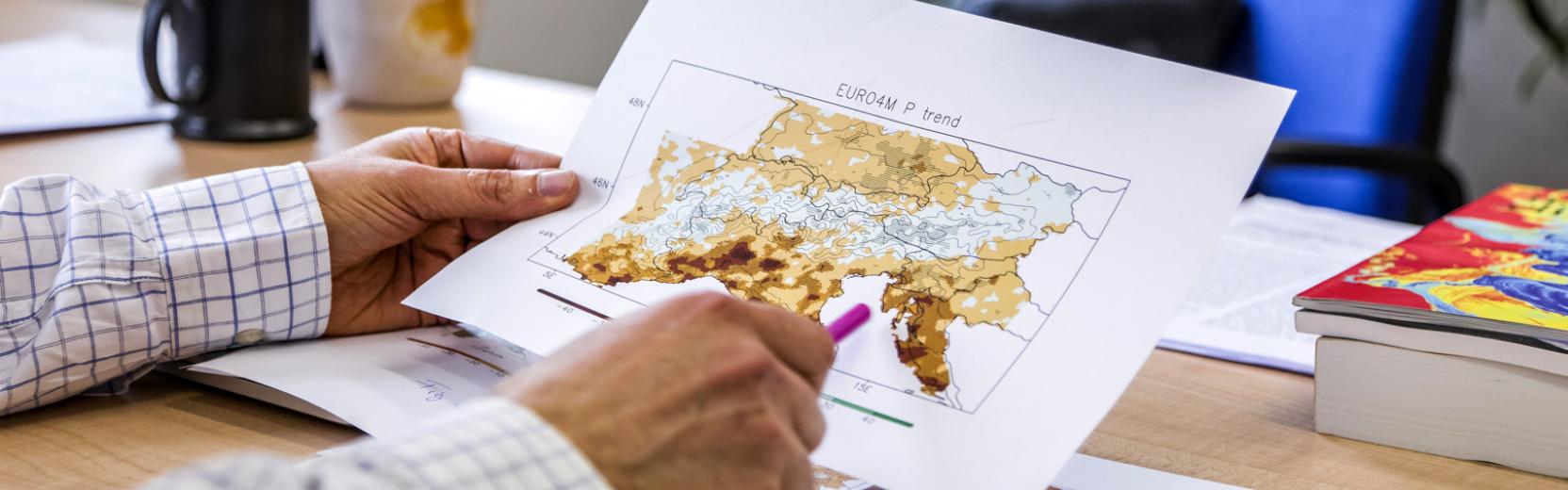

Apart from a personal interest in trying to understand something about sustainability from a quantitative point of view, our group has become involved in a city-wide initiative named the Trieste Laboratory on Quantitative Sustainability (TLQS). This includes 7 groups who are all working on different aspects of sustainability, at various institutes and universities, such as ICTP, SISSA, OGS, and UniTS. In our group, we are essentially studying sustainability issues within an interdisciplinary approach based on statistical physics. In particular, we look into the cracks between what is known, focusing on the interactions among different aspects or subjects, and how one aspect affects another.

How important are collaborations here?

In general, even people in other disciplines appreciate that this type of approach is useful, and it's missing: for example, in cases in which you have a lot of data and it's easy to see what the correlations are, but it's hard to understand the causal effect, or direction. Then, modelling approaches can be helpful.

In other disciplines, there is not so much understanding of our expertise in modelling collective phenomena. There is some in economy, where they use models. Sociology and demography researchers mostly look at the data, and the models used are very simple. In economics, the modelling framework is still very much influenced by the idea of rationality: that you want to trace back collective phenomena to what people are thinking. You have to make a lot of assumptions to do that. Statistical physicists rather rely on stylized models, which make as little assumptions as possible at the microscopic level, and provide robust predictions on what is going to happen at the collective level.

“Complex systems are difficult to model. And it's a big step from understanding the right thing to do to actually doing it.” – Matteo Marsili, senior research scientist with QLS

The other aspect of complex systems like these is that in the end, it is essential to understand the interplay between the human dimension and all techno-natural systems. This is sometimes overlooked.

Complex systems are difficult to model. And it's a big step from understanding the right thing to do to actually doing it. You can just look at what happened with the vaccines and contact tracing app for COVID-19. This is a very interesting example, as it was a failure. Not so much from the technical point of view, the solution was there, but it wasn’t adopted due to resistance because of privacy concerns. So essentially, you could have a society with the best possible intentions, but sometimes it just isn’t possible to implement something.

How do ideas differ between fields?

The differences in how we all approach inequality and sustainability are what make this research so interesting. What I see is there are few disciplinary fights, in the sense that there is a lot of understanding of the differences across disciplines. In this aspect, I would say that the situation has improved with respect to say 15-20 years ago, when physicists were becoming interested in fields such as biology and economics.

How do you use events to address inequality?

Sustainability has a clear relevance for developing countries. Here, it's important that the research agenda is not dominated by developed countries. So, we thought of having a series of events once a year, where we gather together a community of complex systems scientists, people interested applying quantitative tools, modelling and data science approaches to these types of issues.

We had our first event, the Workshop on Quantitative Human Ecology in July 2022, which was very broad across many disciplines, with a central focus on the human dimension and how societies interact. A lot of data on human behaviour is becoming available. For example, we can now study spatial phenomena like movement in cities; how people move. There are also scientists interested in economic systems, and how markets change, or in ecologies, and the stabilities of large ecological systems. In some cases, these can highlight general principles. This workshop was organized with various collaborators, such as the Santa Fe Institute. We then decided to have another workshop, in April 2023, which was more focused on inequality. We invited 20 complex system scientists working on different topics to give talks; mostly physicists who have moved into different topics. The idea was to address inequality from different angles and perspectives.

“There are many trade-offs between diversity and inequality and between stability and efficiency.”

For example, it’s clear that diversity is a good thing; you want to protect minorities, you want to have diversity, but then there is a point at which diversity becomes inequality. What are the structures that sustain this? There are many trade-offs between diversity and inequality and between stability and efficiency. In any case, in order to have a stable society, you should have an organized system with some structure, and this structure implies certain hierarchies. These can be functional, but sometimes they become non-functional. You also find these hierarchies in the animal world, and they are rooted in biology.

The point is to understand inequality from a fundamental point of view. How do we perceive social differences, social hierarchy and social status? What are the relevant circuits in the brain? Because this gives you fundamental limits.

What will the next event focus on?

Our 2024 event will be on collective agency. There is a basic result that shows that designing the perfect society is not just difficult, it’s impossible. The impossibility theorem social-choice paradox developed by Kenneth Arrow in the 1950s illustrated the impossibility of creating an ideal voting structure for a society that aggregates the preferences of different individuals in a rational way. This tells you that there are clearly limits. Not because people aren’t well-meaning; these are just limitations of collective behaviour.

There’s a lot you can learn on this topic from the collective agency that develops in biology, such as plant systems and bacteria, multicellular organisms, and the processes through which cells agglomerate. Different organisms and animal groups have developed different strategies.