Paleontologists, geneticists, and anthropologists have long debated the sequence of evolution and development of ancient humans. Now scientists at ICTP, Federico Bernardini and Claudio Tuniz, as well as former ICTP postdoctoral fellow Clement Zanolli, have added another piece to the puzzle, in a paper published last week in PLoS One.

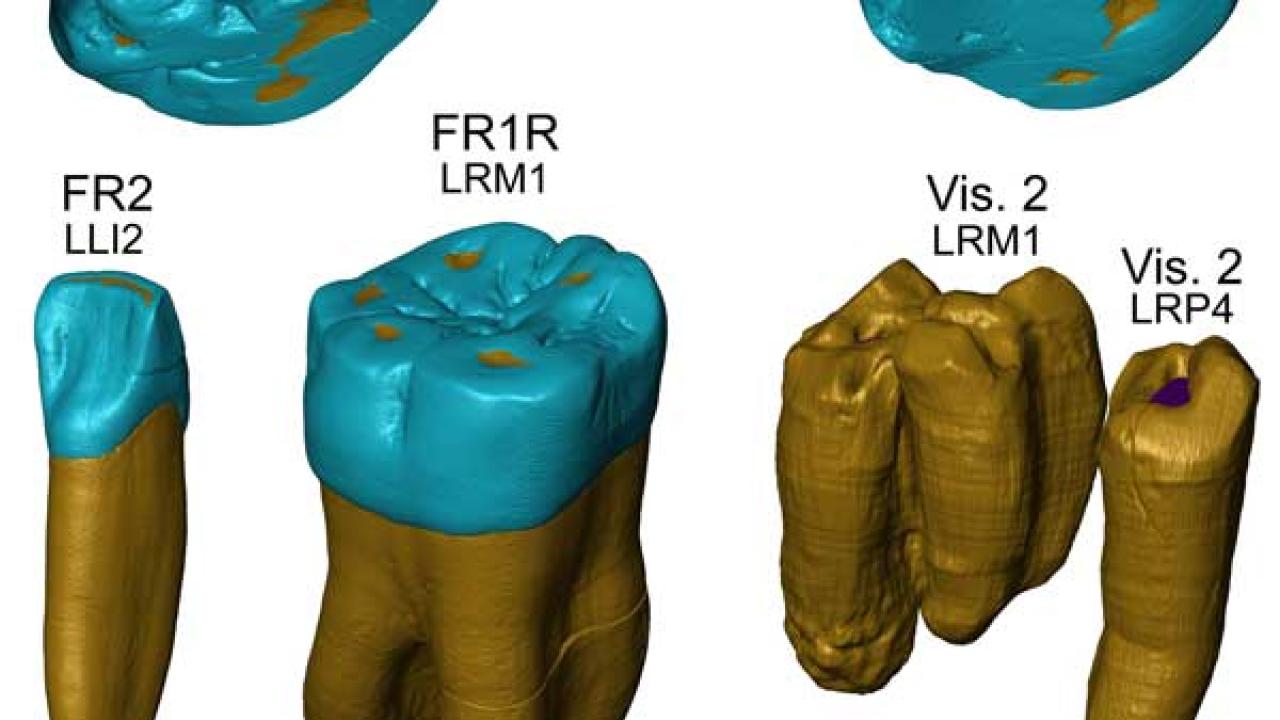

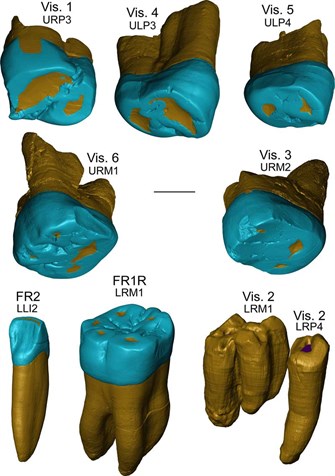

A group of teeth from nearly half a million years ago are the puzzle piece, newly investigated through the specialized microtomography scanner at ICTP's Multidisciplinary Laboratory (MLab). Teeth can hold a large amount of information about their owners. “These are roughly 450,000-year-old teeth. When teeth are very worn, very damaged like these were, microtomography can reveal what’s invisible, what’s underneath the worn enamel,” says Bernardini. What’s underneath is full of details of shape and thickness that reveal much about the species and characteristics of the ancient hominid that the teeth belonged to.

Before this study, it was unclear what species of hominid some of the samples came from. That was particularly true of the ones found in Italy, some very near Trieste, ICTP's home. Based on the age of the teeth, these specimens could either belong to Homo heidelbergensis, an archaic species that is supposed to be ancestral to Neanderthals and modern humans, or to an extinct group that was already part of the Neanderthal lineage.

The specimens are much older than other Neanderthal remains. Neanderthals start to appear in the record starting about 150,000 years ago. That the teeth examined in this study already exhibit Neanderthal traits deepens their evolutionary roots, says Zanolli. They confuse the traditional view of the human tree of evolution: “This is the start of a big discussion about the role of Homo heidelbergensis in human evolution,” says Tuniz.

The specimens are much older than other Neanderthal remains. Neanderthals start to appear in the record starting about 150,000 years ago. That the teeth examined in this study already exhibit Neanderthal traits deepens their evolutionary roots, says Zanolli. They confuse the traditional view of the human tree of evolution: “This is the start of a big discussion about the role of Homo heidelbergensis in human evolution,” says Tuniz.

These early Neanderthal characteristics also muddle the position of modern humans in the evolutionary picture. Previous evidence from DNA pointed towards modern Homo sapiens last sharing a common ancestor with our closest relatives the Neanderthals about 700,000 to 500,000 years ago. Exactly how heidelbergensis is related to Neanderthals and to modern humans is not clear. When more of these very rare specimens are analyzed with new methods, the new data could add more details. The study of the internal tooth structure of specimens that clearly belong to Homo heidelbergensis, like the Mauer jaw found in Germany, could bring some answers.

The messiness of the current picture of human evolution is one of the reasons that tools like the MLab’s microtomography scanner, built in conjunction with scientists at the Trieste synchrotron Elettra, can be so helpful. “We have now analyzed most of the important paleo samples in Italy,” says Bernardini. “This is a very good way to analyze very old specimens without breaking or damaging them, it lets us see inside.” The technique analyzes density differences at a very tiny scale, in this case allowing paleodentists to digitally remove the enamel of ancient teeth and examine the morphology, or shape, of the underlying structure. “Tooth morphology can hold many details, similar to DNA,” says Tuniz.

DNA analysis of this group of teeth is the next step, to continue to gain details that can clarify the picture of human evolution. One of the collaborating institutes on this paper, the Centro Nacional de Investigacion sobre la Evolucion Humana in Burgos, Spain, has already started. “Our colleagues in Spain were not surprised at the results of this paper, as they have figured out new techniques to do DNA analysis on these very old teeth, and have found a number of similarities with Neanderthals there too,” explains Tuniz. “Full-genome exploration is next.”

"I think that a tree of life is not the right metaphor, the right visualization," says Tuniz. "I think it would be more accurate to see it as a river delta, with many rivulets that join together, separate, run out and stop.” Zanolli, a former ICTP postdoctoral and now paleoanthropologist at the University of Toulouse, thinks that the river delta picture could include modern humans and Neanderthals as not nearly as distantly related as previously thought, but as subspecies that could successfully produce offspring. But as Tuniz explains, some scholars have built their careers on a very different picture, leading to the debate.

“These results are controversial,” says Tuniz. Both he and Bernardini hope it encourages other groups to start doing DNA analysis of fossils. “But they bring more support to the idea that human evolution is much more complicated than previously thought.”

Claudio Tuniz will be speaking at the event caffè delle scienze, sponsored by the University of Trieste, open to all on 11 October at 17:30 in Caffe' Tommaseo, Piazza Nicolò Tommaseo, 4, 34122 Trieste TS. Tuniz is the co-author with Patrizia Vipraio of "La scimmia vestita, dalle tribù di primati all'intelligenza artificiale."

----- Kelsey Calhoun