Professor Andrea M. Ghez, a 2020 Nobel Laureate in Physics and the Lauren B. Leichtman & Arthur E. Levine chair in Astrophysics at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), was recently virtually hosted at ICTP on the occasion of the Diploma 30th Anniversary celebrations. Ghez gave a lecture on "Our Galactic Center: A Unique Laboratory for the Physics and Astrophysics of Black Holes", and a keynote address particularly directed to the young students of the graduating class of the 2020-21 Postgraduate Diploma Programme.

Her inspirational words addressed both the difficulties young researchers may encounter at the beginning of their career, and the drive and passions that guided her during her life as a scientist.

In an interview with ICTP, Professor Ghez shared more details about her career and her love of science.

During your keynote address, you described your journey in science in quite an open way. You talked about hard work, doubts and rejections. For example, you mentioned the rejection of your first proposal to use the telescope at UCLA, or the fact that at the beginning of your career you were not confident in public speaking. What guided you through the highs and lows of your life as a scientist?

I think it's really understanding what you have passion for, what you are curious about. It's the curiosity, the desire to know and the passion for what you do. And that's why I really like to emphasize that process of figuring out what is it that you enjoy, because that understanding that you're driven, for some reason, to do this is what gets you over the things that are hard.

Public speaking for example is one of the most common fears that people have. It is definitely one that's really important to overcome and that experience can change. That's why I like to share that story, because it's an example of demonstrating that just because you can't do something in the beginning, doesn't mean that you can't do it at the end of the day. I actually think that a fundamental part of professional development for young scientists is to learn how to do public speaking, and teaching is a really effective way for students to stand up in front of an audience because that's an audience eager to learn; it's a gentle way to get in front of an audience.

It is true that much of the intellectual work of a scientist happens alone, so this is a field that does certainly benefit from people who enjoy thinking on their own, but it's actually a field that is so much more social than we understand when we begin our pursuit or that the public understands. In fact, one needs a fair number of social and communication skills and that's a really big important part of what students learn in post-college institutions: how to write, how to do scientific communication, how to talk about your work to different audiences. I find it really interesting that in college we teach students how to solve problems that answer well-defined questions, and then postgraduate work becomes much more about teaching students how to figure out what the right question to ask is. That's a big shift.

We have to communicate why what we do matters, what is its relevance. And when we are forced to communicate, it also helps us think about what really matters, what are the important problems, how not to get lost in the minutiae of what we do.

What do you think scientists can do to appear less alienated from society, to give a picture of basic science as less separated from everyday life?

This is actually an interesting phenomenon because we live in such a highly technical society. The things that we take for granted are provided to us, and are operating based on a huge amount of science and technology. And so, I think it's super important that we educate people to be comfortable with all this technology that we live with. What can we do about this? I think this is why it's important for us as scientists to talk about what we do and how it relates to people every day. But the basic science is challenging because, by its very nature, it's curiosity-driven and we don't know what the implications are going to be long term. Sharing the history of how things came to pass could help. A classic example is the cell phone, where so much of the technology that enables us to have cell phones today was created with basic research where people really did not understand its long term benefits. It's just critical for us to not have this divide between what we live with, versus the science and technologies that are at the base of these things that we ignore or are afraid of - it's an interesting cognitive disconnect. It's so important to really demystify what science is all about. And this process of collecting information and examining it is so important, especially today with the huge amount of misinformation that is available, what we do as scientists is really what we need to do as individuals. To understand all the information that is provided to us to sift through, that's a scientific process, and yet it's what we need to do every day as individuals: to distinguish, to try to figure out what's fact and what's not.

Black holes are actually one of the topics in contemporary physics research that most interest people. What do you think, in particular, is so fascinating about black holes?

I think, in general, Astronomy and Astrophysics captivate people's imagination, because they tackle the biggest questions that we can ask about our context. We live in this enormous universe, that's so much bigger both in space and time than we are, so I think there's something very fundamental to us humans to understand the context in which we live. I think black holes are fascinating because they just defy our experience: there's nothing on Earth that gives us a sense of the environment of a black hole. Black holes are quite simple objects, and yet they're complicated. Also, I think this is another area in which public communication has helped - shows like Star Trek for example have shown the public some of the intriguing aspects of this field of science. So, I think we have done a great job in the world of astrophysics of intriguing and engaging the public with some of the mysteries that we find fascinating. In some sense, one of the roles Astronomy and Astrophysics can play in society is to be that "hook" to science and technology, to attract and engage in ways that people find fascinating, and to introduce them to the broader realm of science. It's always interesting to see what hooks we can use to bring people from what they're familiar with, and what they're curious about into the next level of what it is that we as scientists are exploring to really get a better understanding of the world in which we live.

What do you think could be the future of the research in black holes? What are your hopes and expectations for this field of investigation?

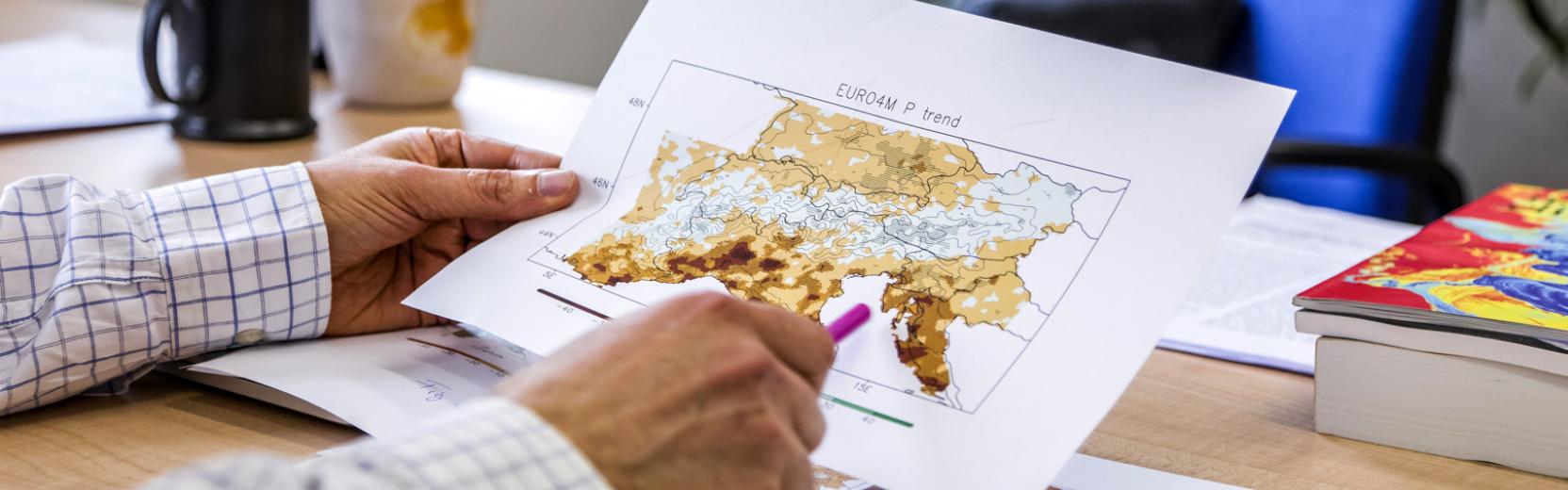

We live in the golden era of astrophysical research because technology is evolving so quickly. There are so many new windows that we've opened up: gravitational waves being a great example of that. And I think we're still in the early days of what we were learning about compact objects from gravitational waves. The Event Horizon Telescope is another facility at radio wavelengths that is opening up to very high resolutions. And then there is the European Extremely Large Telescope. The TMT and the GMT are other facilities that should, once again, open up our understanding of these just incredibly interesting objects from a fundamental perspective, that is, from the fundamental physics perspective, but also to their astrophysical role in galaxy evolution.

Currently, we are working on a number of questions that are now possible to investigate as we now have such a long baseline of observations to really prove for new physics in dark matter at the centre of the galaxy. This particular field is at the moment one of my greatest passions. Then, to understand the potential connection between objects that we see at the centre of the galaxy with gravitational waves or things that are seen elsewhere in the universe, I also find this particularly intriguing. We will be able to make a lot of progress with today's technology, but I also am interested in pushing forward on technology to enable us to make more precise measurements, and to probe deeper into the gravitational potential of the centre of the galaxy, and that will be possible with more advanced adaptive optics systems and the next generation of telescopes. So, those are projects that are near and dear to my heart - they may take decades to build, but they really would change our ability to probe and understand the universe.

You also mentioned the importance of competition and of diversity of point of view to do great science. Do you think that diversity at an international and multicultural level could contribute to better science?

I do. I think that all sorts of ways in which you may think differently, contribute to great advances in science. This is one of the reasons why we encourage our students to move universities from where they were trained as an undergraduate to where they go for their postgraduate work, because even the way your mentors think affects you. By seeing that people think differently, you'll learn that people approach problems from a very different point of view. There is also the benefit of changing fields. One of the examples I love to give is that I had a post-doc who worked with me and decided to go into the finance industry for a couple of years and then decided to come back. We realized that a lot of tools from the financial world were highly relevant to studying black holes, so we ended up doing this project of using those tools to understand how the black hole accretes over time. I think you can find that diversity of viewpoints from all arenas: when you are trained in different countries, when you come from different fields, or different backgrounds, you have the capacity to bring your own individual thought patterns to play. Another way of thinking about this is how people solve riddles, how people solve puzzles. People take very different approaches, there's no right or wrong answer and often the multiplicity of viewpoints really shows the richness of the puzzle. I think that science is just one big puzzle that we're all trying to solve. And that's why I think the diversity piece really works here because we all are exposed to different ideas, and sometimes we don't even understand consciously what we're doing in terms of what unique skills we have that are actually quite different from others.

You are only the fourth female Nobel Laureate in physics. Do you enjoy being a role model, or would you prefer just being recognized for your science merits?

I see myself first and foremost as a scientist. Of course, what I'm an expert in is science, I'm not an expert in gender. So there's nothing special about that per se. I'm delighted that I live in a moment where society is increasingly recognizing and enabling the careers of women, so I'm really happy to be part of opening the door. And opening the doors through just succeeding, because I think that for young scientists to see people who look like you doing what you'd like to do, having role models, is so important. So, I consider myself scientist first because that's my passion. My passion is to do science. And then, I'm grateful that there were people who encouraged me to pursue my passion. I remember reading biographies of Marie Curie that my parents gave to me as a way of encouraging me, and reading that there was a woman who so long ago was recognized for what she did and did so well, while having a family, was so important to me. I think that's an incredible narrative to have out there and yet she was singular for so long. So, I am grateful to be part of another wave that shows that there are now far more women who are doing this kind of work, and are being recognized. I really feel like a lot of the generation before me treated Curie as an exception. While I don't believe that the ability to do science is different between the genders, having a family is a very different enterprise both physically as well as socially for women and men. So I think women are still faced with the choice between pursuing their careers to the fullest or having a family, but I really want to recognize that institutions play an incredibly important role in enabling women to succeed.

During your keynote, you suggested three questions to be asked regularly, and the last one was "What are the opportunities to help others, to give back the help you received during the way?" What would be your personal answer to this question?

I think my answer is constantly evolving but I think it's one of the reasons why I really love doing research in the university context: it's so obvious that the way in which we give back is through teaching the next generation of scientists, being a mentor, providing the same guidance that I received as a young student, to be able to give back to the next generation. The older I get, I also really think about this in terms of helping young professors, just as I also benefited from senior professors when I first started, helping the next generation of people who are coming along their path. I think that, being an academic, it's very easy to think about how to give back, for example through giving talks, or being publicly accessible. It's one of the reasons why I enjoy doing public outreach because I think being visible helps to encourage the next generation to come forward to see that just because you're female or different, it doesn't mean that you can't pursue the things that you are passionate about.

--- Marina Menga