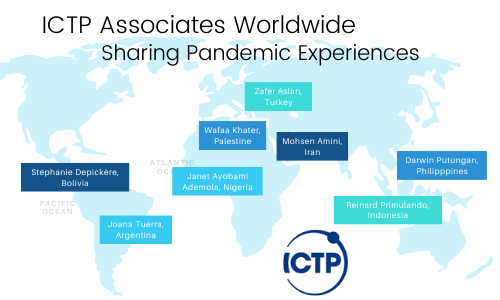

Movement restrictions and cancelled travels: the list of challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic are familiar to all. But for scientists in developing countries, the burden weighs heavily on pre-existing conditions that already put them at a disadvantage, such as poor internet connections and lack of research resources. Interviews with several such scientists who are ICTP Associates based throughout the world reveal a wide range of current worries and circumstances.

The ICTP Associates Programme aims to support distinguished scientists in developing countries, with resources and visits to ICTP for scientific exchanges and workshops, with the goal of building sustainable scientific communities. The overarching reality of the pandemic means that the scientific visits enjoyed by Associates, who are supported for stays lasting from one to three months, have been suspended indefinitely. “I planned to visit the ICTP this year, but it will not be possible with the current situation,” says Stéphanie Depickère, an Associate in Bolivia. “We have had to postpone them until travels are possible again. For now, we cannot go ahead with our project, studying the Chagas disease transmission in indigenous human population and help people to fight the disease.” Zafer Aslan, an Associate from Turkey, was also planning on visiting ICTP in August 2020 with two young PhD students, a visit that is now up in the air and has not yet been rescheduled.

The ICTP Associates Programme aims to support distinguished scientists in developing countries, with resources and visits to ICTP for scientific exchanges and workshops, with the goal of building sustainable scientific communities. The overarching reality of the pandemic means that the scientific visits enjoyed by Associates, who are supported for stays lasting from one to three months, have been suspended indefinitely. “I planned to visit the ICTP this year, but it will not be possible with the current situation,” says Stéphanie Depickère, an Associate in Bolivia. “We have had to postpone them until travels are possible again. For now, we cannot go ahead with our project, studying the Chagas disease transmission in indigenous human population and help people to fight the disease.” Zafer Aslan, an Associate from Turkey, was also planning on visiting ICTP in August 2020 with two young PhD students, a visit that is now up in the air and has not yet been rescheduled.

Travel restrictions are not the only limits that present challenges: lockdowns to different degrees are common. “The health system here is very poor,” says Depickère. “Hence, we are in total quarantine, each person can only go shopping once a week according to their ID number, from 7:00 to 12:00 using mask and gloves.” Lockdowns are imposed in all the countries ICTP’s Associates wrote from: Iran, Palestine, Indonesia, Argentina, Turkey, Nigeria, and the Philippines. “A national emergency was declared and a lockdown was put in place due to the fact that Palestine has very limited resources and a weak health system, which cannot cope with high number of infected people in a short period of time,” says Wafaa Khater, an ICTP Associate working in Palestine. While lockdowns can help health systems deal with the pandemic, working at home, teaching classes online, and the difficulty of continuing scientific discussions online join canceled visits as challenging side effects of the restrictions.

“The most important point is that in the office I am more productive,” says Mohsen Amini, an Associate from Iran. “It seems that the pandemic is going to continue over a long period of time and this will certainly affect my research progress, because now I am working much slower than usual.” For others, working from home is more effective. “Working at home is also peaceful, I do not waste time in public transportation anymore, and I have more time to read articles and participate in scientific webinars organized on the web,” says Depickère.

But teaching online and other demands have severely affected research progress for other Associates. “Since we have not been really trained to do online teaching, the teaching preparation takes longer than for in-class teaching,” says Reinard Primulando, an Associate working in Indonesia. This eats into research time for many. “I have 150 students in three undergraduate courses to teach. I was planning to have some more time for research, but preparations of online course materials take more time,” says Aslan.

“A workshop on Scientific Mobile Learning that I attended in June 2012 at ICTP was particularly useful and came in handy at this time of crisis where I used some of the techniques I learned to improve the quality of teaching my classes remotely,” says Khater. This kind of distant teaching is both a learning experience and a challenge for myself as it is much more time-consuming and labor intensive when compared with the traditional face-to-face teaching. The extra time and effort I spend on remote teaching, in addition to the heavy teaching load we usually have, left very little time to spend on my research.”

“To be honest I have now little time to do research,” says Joana Terra, an Associate in Argentina. “I spend most of the day helping my four children with their homework. In between I have to prepare my own virtual classes for my first year students. I have about 500 students and have to coordinate the work of 10 teaching assistants, besides preparing my own material, answering emails, and so on. Household chores also take a lot of time, even going to the supermarket takes a whole morning. Since doing research involves a more peaceful environment, I am having a lot of trouble finding the right moment.” The difficulty of separating personal and professional life was echoed by many Associates: “The lockdown causes some effects on concentration,” says Aslan. “We have to work at home not only on academic issues but also on daily routines and chores of the house.“

The discussions between colleagues that drive many scientific developments are also hindered by pandemic-related restrictions. “We can now interact via internet,” says Amini. “This is necessary but not sufficient. In particular, I am more worried about my students. They need more interaction with other scientists.” Janet Ayobami Ademola, an Associate in Nigeria, agrees: “Physical contact is better for a meaningful discussion, but this restriction has hindered such interactions.”

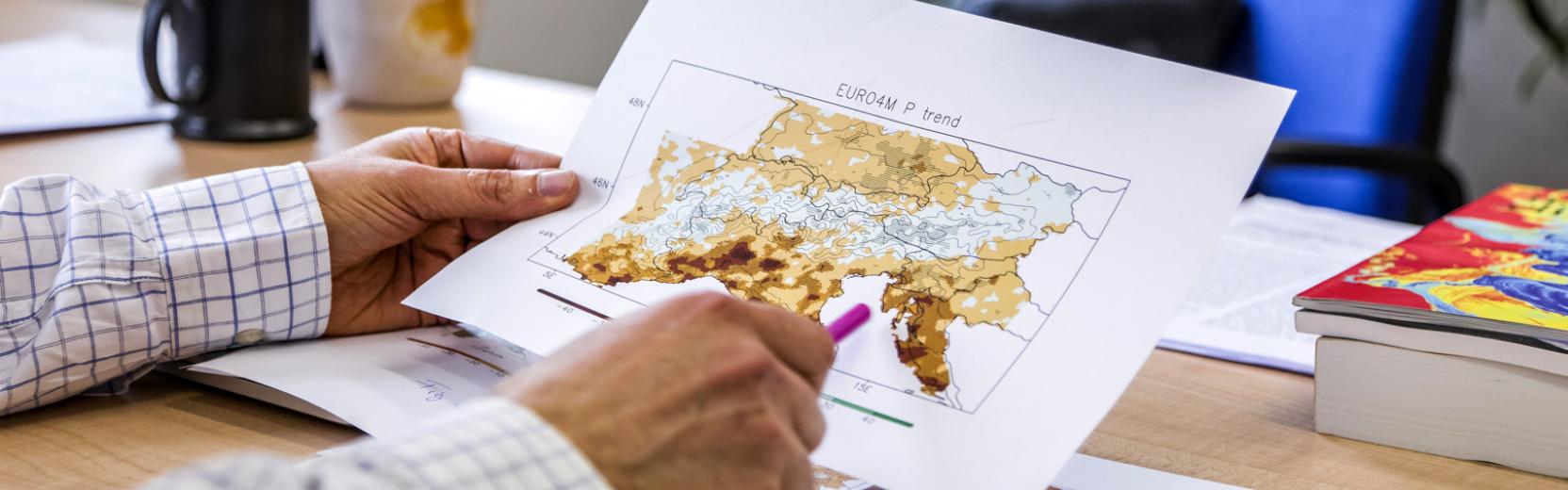

Right now, however, Ayobami Ademola says that access to a reliable and fast internet connection is her main challenge. This issue is common for Associates in many countries, from Cuba to the Philippines. “If needed, we can do online discussions about academic and research matters. However, that is also limited because in most parts of our country, the internet connection quality is not that good,” says Darwin Putungan, an Associate working in the Philippines. “This means student and faculty exchanges could also be stopped indefinitely, resulting in a reduced proliferation of knowledge and expertise that could affect the quality of research outputs.”

As everywhere, the pandemic has exacerbated existing issues and challenges. “The difficulties we usually face here, such as poor access to journals and scientific databases, are not new,” says Terra. “One of my main concerns is the access to important scientific literature in my field of expertise,” agrees Putungan. “Although our university does have subscriptions to some of these, it is quite limited." ICTP’s Marie Curie Library works to counteract this common issue with the electronic Journals Delivery Service (eJDS). The tool allows scientists at institutions in low-income countries to access current scientific literature, mainly in the fields of physics and mathematics, free of charge.

The Associates have other ways to stay connected while adapting to restrictions, including ICTP's virtual seminars. “I have participated in the ICTP online seminars, many thanks for those,” says Aslan, who also suggested discussion sessions between ICTP Associates and other researchers in similar research areas. “ICTP can help by having more virtual seminars. In this way, we can still catch up with the current states of the field,” says Primulando. “If the restrictions happen for a longer period of time, virtual schools might also be considered.”

The long term effects of continued restrictions are on the minds of all, from economic effects, how research may suffer, and how individual careers may be delayed. “If the virus lingers on, the economy might be affected significantly, hence the long-term research funding for my field might be reduced,” says Primulando. “I worry that it will be hard coming back from this ‘pause’,” says Terra. “I had several plans for this semester, regarding my research, which are now suspended.”

But there is some optimism about how scientists can support evidence-based science communication and decision making in the face of the pandemic. “A lot of initiatives are very inspiring, such as explaining to the global population how important it is to flatten the curve in a scientific but simple way,” says Depickère. Ayobami Ademola agrees. “I am impressed by the leading role played by scientists in their effort to finding solutions to the pandemic, which shows the importance of the role of scientists and their research in problem solving.” Putungan echoes this sentiment: “I believe that the academic community would be of great help in these trying times, and that scientists and government officials can work together to solve this crisis. This really inspires me, and I really hope to contribute to these efforts.”

——Kelsey Calhoun