Science often happens slowly but surely, tens and hundreds of scientists working on expanding knowledge piece by piece. Sometimes this long process of hard work culminates in exciting announcements, like the recently revealed first image of a black hole ever made. ICTP’s scientists generally focus on theory rather than the big experimental collaborations that produced this result, but as theorists they have ideas and hopes about what this means for the future of exploring the universe. “This kind of resolution is a magnificent achievement for observational cosmology,” says Atish Dabholkar, a theoretical cosmologist at ICTP.

Previous to this image, the presence of a black hole could only be detected indirectly. Astrophysicists could infer that a black hole was there from the havoc it wreaked on the surrounding matter. More than a hundred years ago, Einstein’s General Relativity predicted black holes as a region of space with gravitational pull so strong that nothing could escape, including light. Einstein was himself unconvinced that they actually existed, and for years they remained a mathematical prediction. “When I was a student, black holes were kind of science fiction,” says ICTP Director Fernando Quevedo, a high energy physicist. “There has been a kind of adiabatic, gradual increase in evidence for black holes in recent years, as opposed to the Higgs, gravitational waves or dark energy, and this is a great new piece of evidence.”

“The theoretical basis for the reality of black holes has been very well established for over fifty years,” says Dabholkar, “based on equations that were discovered a century ago with not a lot of guidance from experiment. At the time, it seemed almost like a fantasy that one would ever be able to make such direct observations of these bizarre objects.”

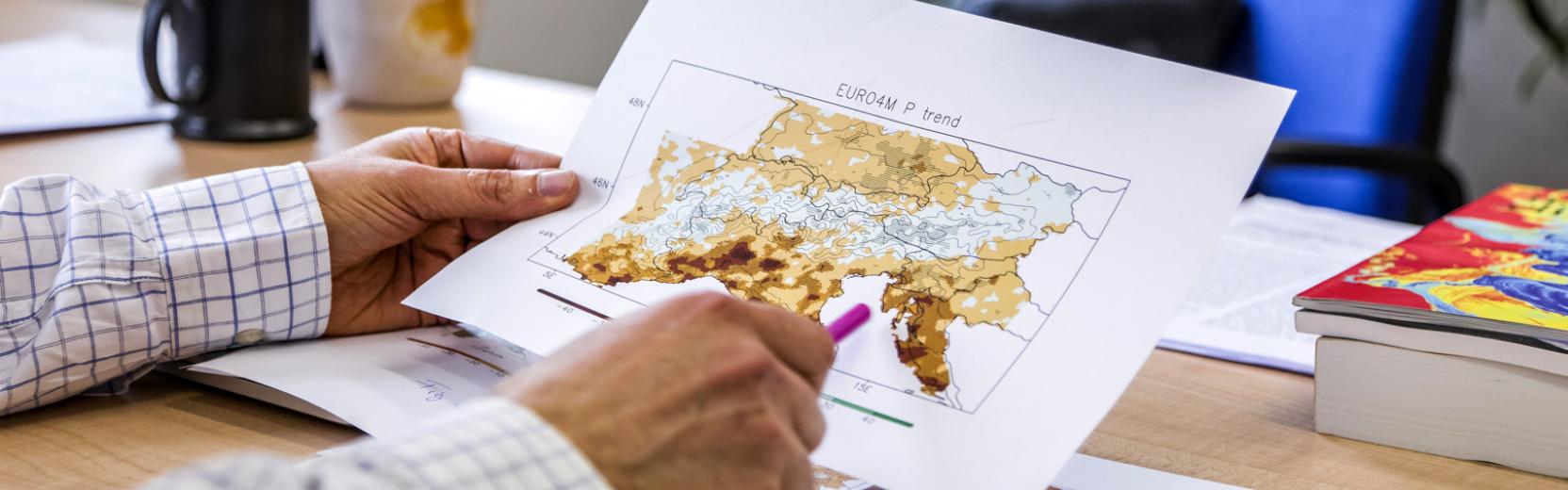

Black holes themselves cannot be seen or directly imaged, as they have such strong gravitational pull that all light and matter are sucked in. But the matter drawn towards the black hole, a mass of dust and gases swirling around it and feeding it, can be imaged, and forms the bright halo around the dark center of the now-famous image. That center holds the event horizon, the metaphorical cliff edge that no light or matter can travel faster enough to escape.

The image was not easy to assemble, even taking into account that this huge black hole is at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, 55 million light years away. Eight radio telescopes around the world, from Antarctica to Chile to Spain, networked together to create a virtual telescope the size of Earth to do the job, called the Event Horizon Telescope. Meticulous coordination between telescopes, weather, and scientists was needed to get this first image of a black hole, including more than 200 researchers working in a large international collaboration.

“For theorists like me, these observations are kind of reassuring that all these abstract calculations that one does on a piece of paper in a quiet office actually have a bearing on a reality as violent as this gigantic black hole devouring stars millions of lightyears away,” says Dabholkar. “It also gives one hope that perhaps the explorations that our generation is engaged in will also someday, maybe a century later, find its place in the description of reality.”

“It’s good to see Einstein’s predictions explicitly satisfied,” Quevedo said. “We may eventually learn some fundamental physics from these observations, and this is only the beginning.”

-----Kelsey Calhoun

Related reading now available in ICTP's Marie Curie Library:

Einstein’s shadow: a black hole, a band of astronomers, and the quest to see the unseeable

by Seth Fletcher

http://library01.ictp.it/F/?func=find-c&ccl_term=sys=000114463&local_base=WEBALL