When does a scientific school become more than a meeting? How does it take on a life of its own? The answers depend on how successfully the meeting has inspired its participants. In the case of the bi-annual African School in Electronic Structure: Methods and Applications (ASESMA), a humble school started eight years ago with the help of ICTP, it has become a dynamic network of condensed matter scientists throughout Africa and the world, making a lasting impact on science development and innovation.

ASESMA’s international organizing committee began with the ideas and effort of South African physicist Nithaya Chetty and his former advisor, American physicist Richard Martin. Chetty aimed to build up connection points and expertise in electronic structure and materials science in Africa. With the key support of ICTP physicist Sandro Scandolo, as well as other top-level theoretical materials scientists from Africa and elsewhere, Chetty and Martin were driving forces in the creation and success of a dynamic scientific community that has earned the respect and support of scientists and donors throughout the world. "ASESMA emerged from the conviction that first-rate science could be done with limited resources by African researchers if they had the opportunity to learn and work side-by-side with others in the global endeavor of science," wrote Martin in a piece for the American Physical Society in 2012.

ASESMA focuses on the study of the atomic structure and behavior of various materials, an important undertaking for a continent rich in natural resources. The field is also an exceedingly affordable one to study: many of the methods it uses require only a desktop computer and ingenuity in order to produce top-quality research. The ASESMA schools focus on those methods, with both lectures and tutorials on specific methods and computer codes available to apply and model theoretical knowledge. A hallmark of the schools is the use of tutors, who are usually senior graduate students or post-doctoral fellows who serve as mentors, working more closely with individual students than lecturers.

"My understanding of electronic structures improved tremendously," says Michael Atambo, an alumni of ASESMA 2012, now a PhD student studying computational materials science at the University of Modena in Italy. "ASESMA includes a lot of hands-on work and one-on-one interaction. You get to work with the experts, not only from Africa, but the best in the field."

For Scandolo, the focus of ASESMA provided the perfect opportunity for him to carry out the educational mission of ICTP: helping to build a sustainable research network in Africa. "Right now the community in the field is small; slowly, slowly it has to be built." He describes ASESMA’s ten-year plan that aims for a school to be organized every two years, nurturing the development of materials science expertise. "From students to mentors to eventually professors - that's the goal," he explains.

Many people and organizations have supported the ASESMA network and schools, including the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) and host universities. Scientists from across the North America, Europe, Africa, and Japan have funded their own travel to lecture at ASESMA. "It's easy to recruit lecturers," says Scandolo. "Colleagues frequently approach me- it's an opportunity to do something useful with their specific skill set."

But organizer Martin is quick to point out a key contribution coming from ICTP, in addition to some funding. "ICTP and the Quantum ESPRESSO team are real leaders in developing codes, especially for one of the most widely used methods in physics, Density Functional Theory (DFT). And they're some of the few groups in the world to make tutorials for using those codes, and to make those tutorials open access."

"If you know the theory and not the applications, you are far behind," says Bamidele Ibrahim Adetunji, a lecturer at Bells University of Technology in Ota, Nigeria. "ASESMA has tried to bridge that gap, and enables students to publish in good journals by teaching techniques for research." Adetunji attended the 2012 ASESMA school in Kenya as a student, and returned to the 2016 school in Ghana as a tutor, after a PhD studying semi-conductor materials. He adds, “One of the lecturers taught me a technique in ten minutes that I use all the time today, and that knowledge has been spread to my students. Students are now coming to me from different parts of Nigeria to learn these concepts."

"ASESMA brought another view of science," says Anne Etindele, a lecturer at the University of Yaounde in Cameroon, who attended in 2012 as a student. "It's based on sharing and building a network among people working in different domains, developing concepts for students, laying it out step by step."

Local organizers in condensed matter groups across Sub-Saharan Africa are active and energetic, not only in organizing conferences but keeping the network going between schools. That's one of the biggest challenges at the moment, says Scandolo. Other challenges include lack of research time and support for scientists at many universities in Africa, with teaching prioritized. Mobility is another, with it sometimes being cheaper to get from Ghana to Italy than from Ghana to Kenya. That can hinder collaborations and network building, as face-to-face interaction is crucial for teams of scientists working together.

But despite these challenges, the community of condensed matter researchers in Africa is growing. Both Scandolo and Martin mention the drive of two other organizing committee members, George Amolo, of the Technical University of Kenya, and Omololu Akin-Ojo, of the African University of Science and Technology, whose research has attracted many more condensed matter physics students in recent years.

"The goal of ASESMA is building connection points, building up expertise," says Martin. It's a slow process, but one that has already seen success, not only in the long list of papers published by ASESMA alumni, but also in the number of alumni that have gone on to do PhDs. The connection between ASESMA and ICTP has remained strong, with several ASESMA alumni taking part in the Centre’s Diploma, TRIL, STEP, and Associate programs. Adetunji was himself a STEP student during his PhD, and Atambo was a TRIL Fellow.

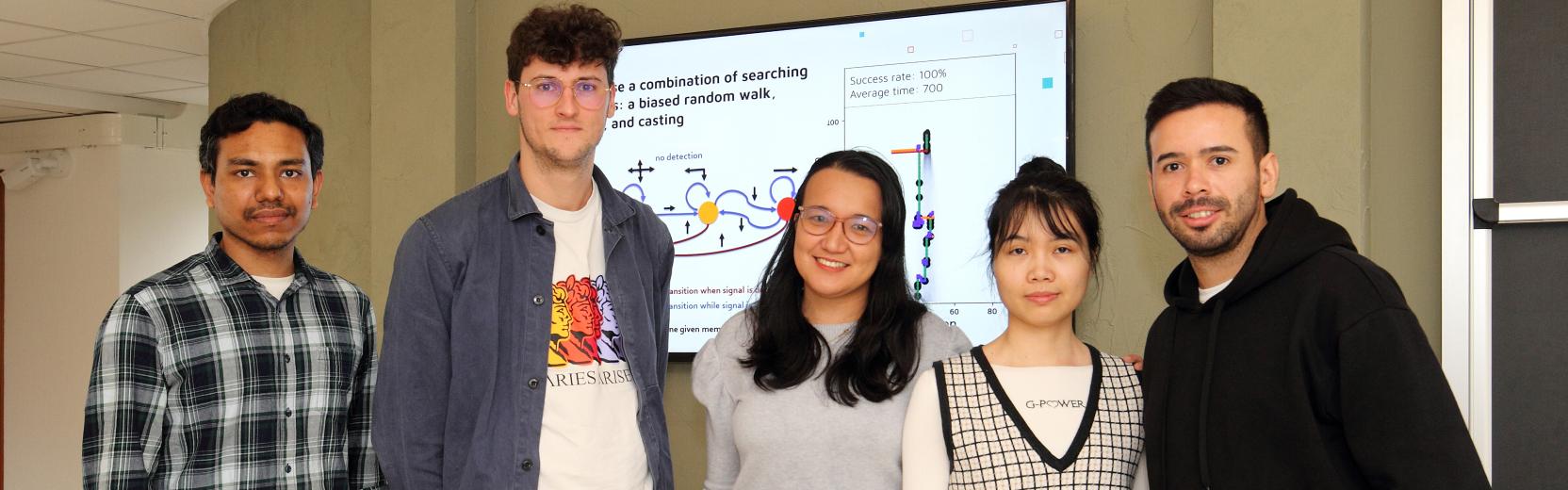

"It's a very different type of conference," Etindele says. "There's free discussion - everyone is very accessible and it's easy to ask questions. Usually there's a gap between lecturers and students, but at this school everyone is having fun together." That community is something Scandolo is proud of, something that was deliberately aimed for, says Martin — one of the prizes given out at the end of each school is for the 'most joyous' participant. "It's a community," says Scandolo. "People who meet at conferences, who continue to meet at conferences, form friendships and personal connections. The fact that this community is being created is the most important aspect of ASESMA."