The end of the year is a good time to look back at some of ICTP's 2017 highlights. Among all the conferences and schools that the centre runs, a June activity called the Climate, Land (Food), Energy and Water strategies (CLEWs) Summer School on Modelling Tools for Sustainable Development stands out. It was unique in several ways: it focused on open-source modeling tools, and its attendees were government analysts and academics involved in policy making in their respective countries. Two-and-a-half weeks of training were accompanied by several days of a high level meeting, all with the goal of boosting modeling skills and modeling's place in policy making for sustainable development.

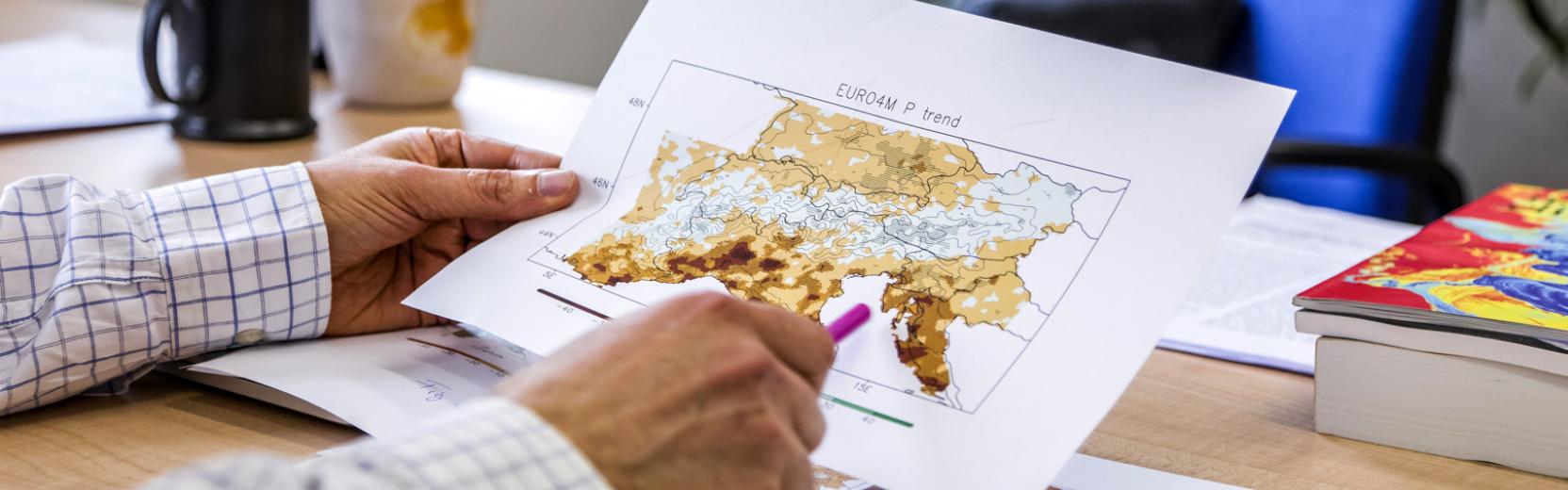

The school organizers want to help countries tackle issues together, as no issue exists in a vacuum. The five school co-directors and their respective agencies have been working on open source tools for modeling different issues, especially energy and water. "Adrian [Tompkins, ICTP climatologist, school co-director] and ICTP have a humming programme of modelling climate change impacts, and so this is probably the only place you can go to get this suite of open source tools without all the usual barriers to entry for developing-country analysts and scientists," said Mark Howells of the KTH Royal Institute of Technology of Sweden, a co-director of the school. He and the other co-directors have helped organize schools like this one, in conjunction with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA), to make it easier for policy makers to have access to the latest data and research, believing that evidence-based, science-based policy is better policy. "It's clear that land use, water use, all these issues are linked, but there are very few modelling tools out there to help governments do the numbers so they can see how they're linked," said Howells. That's where CLEWs comes in.

"This whole thing started with a paper that was published in Nature Climate Change, where we did the first CLEWs model for Mauritius, and one of the clear findings was that one of the policy lines they were on was potentially self-destructive," explains Thomas Alfstad of UN-DESA, one of the school co-directors. Mauritius was considering shifting from sugar manufacturing to biofuel production, but models revealed there would be unintended negative side effects. The island nation of Mauritius has a water table that is becoming salinated, while the island imports most of its energy, mostly fossil fuel energy. With climate change, water shortages would only increase. Farming biofuels would require expensive irrigation and desalination with even less electricity available, because hydrostations would be out of commission. "It would create chaos," Alfstad said. "So, something that looked like a really good policy — more biofuel — would be destructive from a number of points of view."

For many countries, sustainable development is as incredibly complicated as it is in Mauritius. While business-as-usual policies are unlikely to help countries meet the ambitious United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to reduce disease, poverty, illiteracy, and pollution, there is no clear path ahead. "The SDGs are not 17 separate ambitions, but highly interlinked challenges that require coordinated action," said Howells.

Modelling is a relatively new tool for policy makers, a departure from traditional policy making. Part of the goal of the CLEWS school was to make modelling an easy-to-use tool for tackling the SDGs. "We want to help the analysts to convince the upper level policy makers that modeling is useful to inform decision making. You have to allow your people to take time from their regular duties to run models, or to make this a regular duty," said Hans-Holger Rogner, recently retired from the IAEA and one of the school's co-directors.

"It's important to understand how policy decisions are made," said Eduardo Zepeda Miramontes of UN-DESA, one of the co-directors. "In some cases, some policy makers check with astrologers before they make a decision. So now some policy makers can check the models before they make a decision." Rogner agreed: "Policy makers have advisors, and the model is one of the advisors."

CLEWs was designed to train government analysts and policy advisors to be the bridge between pure research and the political arena of policy making. The first two weeks of the school were comprised of nearly 100 hours of training in various modelling techniques. "We put the technical people to work, to train for two and half weeks, very intensively, and then we ask their superiors, sometimes ministers who are quite high, to come and discuss the use of modelling, with the concrete input of these last two weeks," said Zepeda Miramontes. All the conference attendees had a background in modelling of some type or another, and courses helped them tailor their skills specifically to policy making. They represented different sectors of their government, sometimes specializing in energy management or land use. This way, no participant represented their country alone: participants could start to build bridges between issues.

CLEWs dovetails nicely into ICTP's capacity building mission. "This meeting was great in that it culminated in this high-level segment where there were ministerial-level people, who are there to say, we want the best science to inform policy, and it's not every day that that happens," said Howells. Alfstad continued: "We see in many places that there are a lot of policy aspirations, but to move from aspirations into something you can action you need numbers, and these models are great for getting these numbers out."

“There are two elements we’re hoping the participants leave with,” said Alfstad. “One, the ability to show and convince their bosses that modelling is useful, and two, the ability to deal with data, and manage that knowledge.” All of the software used for the school was open source, tools that have helped modellers in a variety of positions publish research frequently over the last few years. Being able to publish means analysts can advise their governments while maintaining a role in knowledge and technique development in the field of sustainable development modelling; their knowledge does not stagnate. Besides being able to use and teach colleagues about open-source tools, the network the school creates among participants, ministers, and academics will hopefully serve as a tool on its own, a resource for working science into policy making.

"This workshop was quite useful in that it helped policy makers trust modelling," said Semu Moges of the Addis Ababa Institute of Technology, one of the invited guests at the high level meeting that concluded the school. "It's not common for UN agencies to talk to academics and governments at the same time," said Callist Tindimugaya of the Ugandan Ministry of Water and Environment. "It's been very fruitful. The format of ICTP really facilitates that discussion, we feel at home." Both ministers stressed the need for more dialogue like this one, covering how this good work can move forward into policies. "There is a strong need for integrated policies, we can't achieve the SDGs without an integrated approach across sections and issues, and we need to move to more science-based policies," said Tindimugaya. "Modeling can help with that."

Photos from the CLEWs Summer School can be found here.

----- Kelsey Calhoun