With the 2015 Paris Climate Conference days away, an ICTP multidisciplinary conference focusing on climate came at an opportune moment, bringing researchers together in Trieste to tackle the challenge of understanding the complexities of a variable and changing climate. The two-week conference and workshop, co-organized with CLIVAR (Climate and Ocean: Variability, Predictability and Change), was dedicated to examining decadal climate variability, spotlighting a smaller timescale that has recently been getting more attention.

The conference drew scientists from around the world who represented a wide range of fields within climatology. Some specialists focus on specific regions, from the North Atlantic to the Polar regions. Other researchers devote their time to specific climate components, isolating the atmosphere, oceans, or the world's ice, known as the cryosphere. Another community of scientists at the conference study the best ways to measure climate variability, figuring out improved methods to collect the large amounts of data used for modeling.

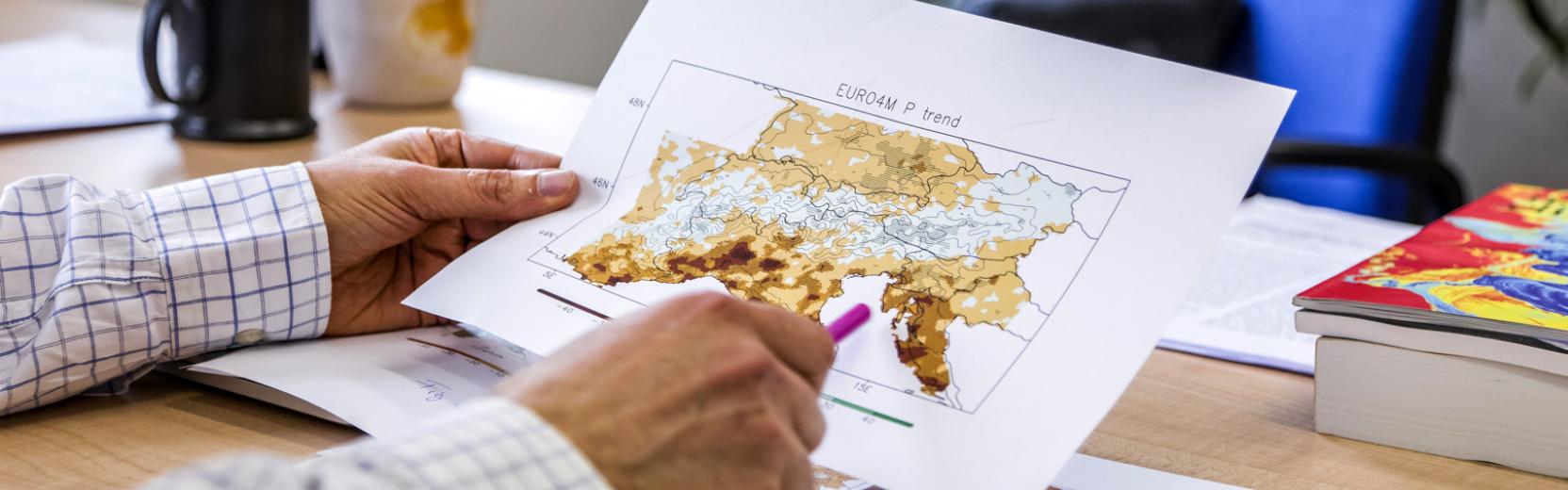

Most, if not all, climatologists use climate models in some way. The models are giant computer simulations that try to take into account as many temperature variations, wind shifts, pressure changes, and precipitation levels across the globe as possible in creating an overall picture of the Earth's climate. More than forty models are currently in use by researchers, all slightly different, but often related. Many of these models comprise the same components plugged together in different formations, looking for the combination that best predicts what actually happens.

One of the chief challenges of verifying the strength of these models is the limited amount of data to check them against. "We only have very short temperature records in most areas, and we see these decadal variations but we don't necessarily know if they happened in the past," explains Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading. Paleoclimatologists at the conference brought their expertise on past climate to bear on decadal variability across the last two thousand years. This knowledge is derived from a wide range of sources, including tree rings, ice cores, cave stalagmites, corals, and historical documents.

"The only way for us to test models is to look in the past," says Fred Kucharski, ICTP scientist and conference co-organizer. "If we talk about weather forecasts, we can verify it tomorrow. If we talk about decadal climate forecasts, we have only so much time in the last hundred years, so one idea is to try to verify decadal predictions back in the past."

The upcoming Paris conference and the growth of paleoclimate data are not the only reasons the ICTP conference is especially pertinent now. A new body of data has recently become available from the Argos observations system deployed worldwide. This system provides a more detailed picture of worldwide climate, via an increase in observation points throughout the oceans, land, and atmosphere. Argos provides the most comprehensive monitoring of the ocean to date, from the surface down to a depth of two kilometers. Ocean surface salinity measurements are also now available, provided by new satellite technology.

More observational data and better paleoclimate data will help climatologists tease apart what constitutes natural climate variability and human-forced variability. "Climate change is all about energy balance; we get energy from the sun and then reemit it as infrared radiation," says Hawkins. "Without human activity there would be 365 days of solar energy going in, and 365 days going out, but we're keeping half a day's worth of energy every year--you can measure that from space." You can see this in the rise of sea levels and ocean surface temperatures, Hawkins explains, which are symptoms of this rearrangement of heat. But when examining climate patterns across decades, it's difficult to determine how natural and human changes influence climate variability, and how models can best predict that.

"Predicting what's going to happen in the next decade is not a straightforward thing, in some cases it may never be possible in the sense of predicting daily weather or even in the prediction of El Niño," says Yochanan Kushnir, a conference co-organizer from Columbia University's Earth Institute, explaining the chaotic number of variables that go into determining one day's weather. "So we also have to consider that challenge, and figure out how to still be able to provide useful information," to all sorts of users, from conservationists, municipal resource managers, farmers--anyone who wants to try to make plans in the face of climate change.

--Kelsey Calhoun